The marketers claim a diamond is forever.

And sure, it's a hard stone. It lasts a long time.

But what about financially? Is it equally durable? You've just sunk a small fortune into those rocks you're giving on Valentine's Day. Are they likely to hold or gain value over time?

I decided to investigate. And the results, alas, aren't sparkling.

Even before looking at all the transaction costs, diamonds have proven an absolutely disastrous investment for decades.

According to the Rapaport Diamond Index,

a respected industry benchmark, prices of top-quality stones have

collapsed by as much as 80% in real, inflation-adjusted terms over the

last 30 years. Even if you set aside the short-lived but massive price

bubble back in 1980—around the time of a similar bubble in gold and many

other commodities—the results have still been abysmal.

The index has been measured since 1978 by Martin Rapaport and his firm, the Rapaport Group,

which provides a variety of research and trading services to the

gemstone industry. The index looks at prices for top-quality one-carat

stones, those with the best color and clarity. While every stone varies, in 1978 a typical such stone, according to the index, cost around $6,100. Today it costs nearly $11,000.

On the surface, that looks like a gain. But investors are frequently

fooled by the effects of inflation. Taking that into account, the stone

has actually lost about half its value in real purchasing power.

Stone prices peaked in 1980 at about $60,000 in today's money. Some store of value.

After the crash in the early 1980s, prices bottomed out in 1985 at about $9,600

in today's money. Since then, in real terms, they've barely edged up.

They have, at least, kept up with inflation. But that's ignoring all the

related transaction costs, from broker's fees and commissions and retailer markups on buying and selling to insurance costs.

Never mind that during the same period, anyone investing in a

broad-based stock index fund—or even government bonds—made many times

that money.

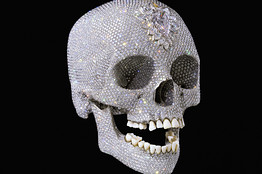

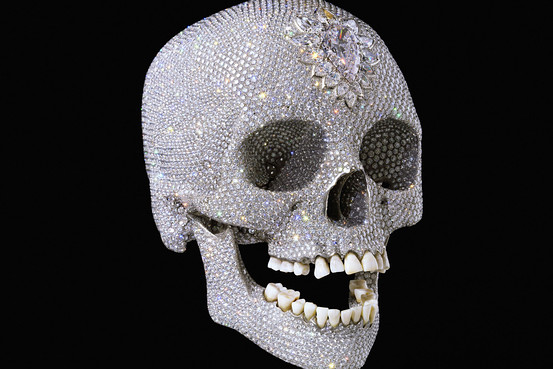

Getty Images

Artist Damien Hirst's platinum cast of a human skull, entitled "For the Love of God," is covered with 8,601diamonds.

Diamonds

are a marketing gimmick as much as anything else. Most men feel they

have to give a diamond ring when they propose—even though, as anyone

knows after a moment's thought, the only woman worth buying a ring for

is the one who doesn't care how much you spent on her ring. (In

Shakespeare's "Merchant of Venice," I might add, the successful suitor is the one who picks lead over silver or gold.)

The biggest winner in the diamond game is the Oppenheimer family, which runs De Beers, the Standard Oil of the diamond world. The company dates back to Cecil Rhodes and the Victorian era, and once controlled nearly 90% of the world's diamond business. It is still by far the biggest player. (Annual results, out this week, showed sales and profits tumbled across the industry as a result of the recession. But De Beers

has merely responded by cutting production and costs. Rising demand

from the newly rich in emerging markets means the future looks bright.

And the company had no difficulty raising a quick $1 billion from its investors to pay off some debts. Life is good at the top, even when times are tough.)

Nicholas Oppenheimer, the billionaire in charge of the company, admitted this week that most of the sales growth in the U.S. over the past decade has been the result of clever marketing campaigns.

There's no logical reason why you should have to cut a check to Mr. Oppenheimer's

family, or even to their competitors, in order to ask your girlfriend

to marry you on Sunday. But you probably will anyway. Most of us do.

Marketing is a powerful thing.

(If you are doing so, Russell Shor, senior industry analyst at the Gemological Institute of America, has some advice. Pear-shaped diamonds

can often seem bigger than round ones of the same number of carats, he

says. And small differences in clarity are often less visible to the

naked eye than differences in color.)

But you're much better off selling diamonds than buying them. The numbers tell the story. Anyone who invested $1,000 in the Tiffany & Co. IPO in 1987 and just sat back and left their money alone, merely reinvesting the dividends, would have about $26,000 today. Someone who sunk that money into diamonds instead: less than $2,000.

Anglo American, the South African mining company that owns a major stake in De Beers,

has been a terrific investment for decades. Investors in the stock more

than tripled their money last decade—while diamond prices rose by less

than a third.

Has the longer-term picture for diamonds been any better than that of the last 30 years? Reliable data are hard to come by. Mr. Shor

says historical studies show modest price gains before the 1970s boom.

"Until the 1970s, prices were relatively stable, trending upwards," he

says. "in the mid-1970s, we had a lot of inflation. Diamonds, all of a sudden, soared in value."

If the past is prologue, which past? If we see soaring inflation and

negative real interest rates again, as we did in the 1970s, diamonds and other hard assets might even take off again. But with investments, as with love, there are no guarantees.

Write to Brett Arends at brett.arends@wsj.com

![[ROI0021110]](DiamondsArentAnInvestorsBestFriend_files/OB-FP067_ROI002_NS_20100211185354.gif)

![[timessquare_101]](DiamondsArentAnInvestorsBestFriend_files/OB-QD002_timess_A_20111015182319.jpg)

![[g20_1015_01]](DiamondsArentAnInvestorsBestFriend_files/OB-QC974_g20_10_A_20111015113558.jpg)

![[1015occupy15]](DiamondsArentAnInvestorsBestFriend_files/OB-QC978_1015oc_A_20111015121449.jpg)

![[METRO1]](DiamondsArentAnInvestorsBestFriend_files/NY-BG165_METRO1_A_20111014191054.jpg)

![[JBASEBALL_7]](DiamondsArentAnInvestorsBestFriend_files/P1-BC994_JBASEB_C_20111014185701.jpg)

![[OZRUBBER]](DiamondsArentAnInvestorsBestFriend_files/WO-AH406_OZRUBB_C_20111014175820.jpg)

![[Seal]](DiamondsArentAnInvestorsBestFriend_files/NA-BN726_Seal_C_20111014164314.jpg)

![[freedeco2]](DiamondsArentAnInvestorsBestFriend_files/OB-QC448_freede_C_20111013181647.jpg)

Most Recommended

“These protesters have no idea wh...;”

“"Movements built on hatred...;”

“Anyone who takes more than 10...;”

“What's scary is that these peopl...;”

“Mr. Cain's strength is found in...;”